![[box cover]](../../reviewimgs/c/charleybowers.jpg)

Charley Bowers: The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius

Charles R. Bowers is the Mysterious Stranger of early screen comedy. The details of his life are sketchy. We know that he was born in Iowa in 1889 (the year Charlie Chaplin was born in London). A 1928 press book bio claims that his parents were a French countess and an Irish doctor, that at age five a tramp circus performer taught him to walk the tightrope, and that at six the circus kidnapped him, after which he didn't return home for two years, when the shock killed his father. It's a dubious but entertaining story. We do know that between 1916 and 1926 he wrote, produced, and directed hundreds of cartoon shorts based on the "Mutt & Jeff" comic strips.

Charles R. Bowers is the Mysterious Stranger of early screen comedy. The details of his life are sketchy. We know that he was born in Iowa in 1889 (the year Charlie Chaplin was born in London). A 1928 press book bio claims that his parents were a French countess and an Irish doctor, that at age five a tramp circus performer taught him to walk the tightrope, and that at six the circus kidnapped him, after which he didn't return home for two years, when the shock killed his father. It's a dubious but entertaining story. We do know that between 1916 and 1926 he wrote, produced, and directed hundreds of cartoon shorts based on the "Mutt & Jeff" comic strips.

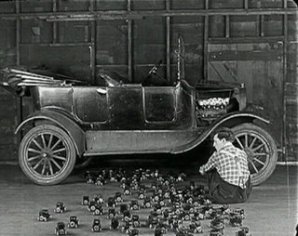

Then in '26 he created a short film that fused live action with lunatic stop-motion animation. Titled "Egged On," it involved an inventor who builds a Rube Goldberg contraption that renders eggs unbreakable. At its climax, a basket of chicken eggs, warmed on the engine of a Model T Ford, hatch open — and out pour a gaggle of tiny Model T's that unfold like origami and trundle around mama Ford until she snuggles them beneath her chassis. The scene is weird and giddily funny.

Other screen burlesques displaying that oddball creativity soon followed. We can wonder if young Theodor Geisel (later known as "Dr. Seuss") pocketed inspiration while watching Bowers' inventive visual jabberwocky. Likewise we can imagine these films hinting at what might have been if Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel had blended surrealism with gonzo humor.

But today, if not for a few dogged historians and old tins of footage scattered across Europe, Bowers would be utterly forgotten, one of America's lost independent filmmakers.

Now Image Entertainment in the U.S. and Lobster Films in Paris have teamed up to bring 15 surviving Charley Bowers films to DVD. Besides "Egged On," we get others that blend live action and fluid three-dimensional animation.

In "A Wild Roomer," a brazenly elaborate 24-minute masterwork from 1926, he invents a white-gloved mechanical monstrosity that bathes, manicures, dresses, and feeds its owner. It's controlled via a push-button console attached to a comfy sofa, presenting modern electro-conveniences presaging "The Jetsons" by two generations. When Charley "drives" the giant machine through his workshop's wall and into the (quite real) city streets, we get some of silent cinema's more peculiar scenes of creative whimsy. We can only imagine what the local residents and shopkeepers thought about the goings-on filling their streets when Bowers brought his robotic behemoth chugging to town with a camera crew. Charley demonstrates the machine to his boo-hiss villain uncle, who for reasons of his own has tried to blow up the contraption by tossing anarchist cherry bombs while the machine was en route. The uncle, who, as God is my witness, looks like Bela Lugosi in Plan 9 From Outer Space, ultimately gets trapped in, and suitably abused by, the machine's arms while Charley's auntie plays with the hand-labeled knife-switches. The switch marked "Egg Shampoo" is a high point.

In "A Wild Roomer," a brazenly elaborate 24-minute masterwork from 1926, he invents a white-gloved mechanical monstrosity that bathes, manicures, dresses, and feeds its owner. It's controlled via a push-button console attached to a comfy sofa, presenting modern electro-conveniences presaging "The Jetsons" by two generations. When Charley "drives" the giant machine through his workshop's wall and into the (quite real) city streets, we get some of silent cinema's more peculiar scenes of creative whimsy. We can only imagine what the local residents and shopkeepers thought about the goings-on filling their streets when Bowers brought his robotic behemoth chugging to town with a camera crew. Charley demonstrates the machine to his boo-hiss villain uncle, who for reasons of his own has tried to blow up the contraption by tossing anarchist cherry bombs while the machine was en route. The uncle, who, as God is my witness, looks like Bela Lugosi in Plan 9 From Outer Space, ultimately gets trapped in, and suitably abused by, the machine's arms while Charley's auntie plays with the hand-labeled knife-switches. The switch marked "Egg Shampoo" is a high point.

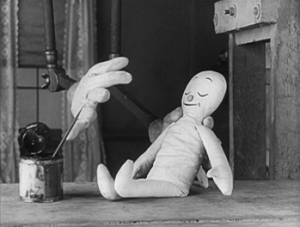

There's not much we'd call narrative in "A Wild Roomer." Amusing spectacle is the main goal, and that's one of the reasons Bowers doesn't reach the Olympian genius of Buster Keaton, an obvious inspiration. But Bowers doesn't give us just chuckles and mechanical gosh-wow. His clanking iron beast — well, we can easily imagine hearing its clanking, whirring life over this disc's new jaunty piano score — brings its own beauty when it in turn bestows life in the form of a stuffed fabric puppet that awakens with the beating of its own newly created cloth heart. The machine even fashions its child a set of clothes when the puppet realizes its own Edenic nakedness. Bowers' skill as an animator, and his knack for naturalistic timing while doing it, is extraordinary here. The detail we see in the machine's gloved fingers as they interact with the puppet's expressive face (and wiggling toes when it's putting on its shoes) displays a lovely feeling for nuance and character. Machines (or machine-creatures) generating artificial life of their own is an image Bowers delivers several times in his films, and no doubt a film-school thesis could come from exploring this comical-bizarro poetic representation of the industrial age.

One of the most eye-poppingly inventive films of the silent era is Bowers' "Now You Tell One." A gentlemen's Liar's Club, "The Citizens United Against Ambiguity," has convened for its latest telling of tall tales. Bowers takes the prize as an inventor botanist who has developed a potion that will "graft anything." So through astounding stop-motion animation effects, we're treated to witty gags worthy of a Tex Avery cartoon, such as an eggplant tree that sprouts hardboiled eggs complete with salt shaker. When the home of his would-be girlfriend is besieged by mice (one of which wards off her cat with a tiny revolver), he harvests cattail plants and grows an army of rodent-battling felines — one of the oddest, possibly one of the most creepy-funny stop-motion animation scenes from the age before Ray Harryhausen. Also, note the scene where Charley drives a herd of elephants and donkeys into the Capitol building in Washington D.C. It's said that the trick photography so fooled the higher-ups that they demanded an investigation (after all, this was an age of "the camera doesn't lie"). Charley and the pachyderms, of course, had never actually stormed the District of Coolidge.

One of the most eye-poppingly inventive films of the silent era is Bowers' "Now You Tell One." A gentlemen's Liar's Club, "The Citizens United Against Ambiguity," has convened for its latest telling of tall tales. Bowers takes the prize as an inventor botanist who has developed a potion that will "graft anything." So through astounding stop-motion animation effects, we're treated to witty gags worthy of a Tex Avery cartoon, such as an eggplant tree that sprouts hardboiled eggs complete with salt shaker. When the home of his would-be girlfriend is besieged by mice (one of which wards off her cat with a tiny revolver), he harvests cattail plants and grows an army of rodent-battling felines — one of the oddest, possibly one of the most creepy-funny stop-motion animation scenes from the age before Ray Harryhausen. Also, note the scene where Charley drives a herd of elephants and donkeys into the Capitol building in Washington D.C. It's said that the trick photography so fooled the higher-ups that they demanded an investigation (after all, this was an age of "the camera doesn't lie"). Charley and the pachyderms, of course, had never actually stormed the District of Coolidge.

In "He Done His Best" Charley builds a machine that performs all the chores at a restaurant, from cooking to setting tables to serving.

Only the second half of "Say Ah-h!" exists, but we still see Charley feeding an ostrich food ground from a broom, a hoe, a pillow, clothes, and a feather duster, after which the ostrich lays an egg that hatches an ostrich constructed of those items. The surreal creature eats everything in a shed, including a metal stove, and dances to a phonograph record. Similarly, in 1930's "It's a Bird," the only talkie Bowers starred in, he plays a junkyard employee who captures a rare bird that eats metal. The talking bird is a marvel of bizarre puppet animation, equaled only by a full-grown automobile hatching from its egg.

If "It's a Bird" looks like source material for the 1938 Looney Tunes masterpiece, "Porky in Wackyland," then two of Bowers' clay animation films from 1940 — "Wild Oysters" and "A Sleepless Night" — might have inspired Chuck Jones with their family of house mice conniving to evade the cat or snag some cheese (although the sight of oysters shucking their own shells to assault a mouse is a unique oddity).

Other films here include a peculiar oil industry promotional short, "Pete Roleum and His Cousins," that Bowers and director Joseph Losey made for the 1939 New York World's Fair.

(Note: Not included on this DVD, but worth mentioning all the same, is the 1928 short "There It Is." Directed by Harold L. Muller, it stars Bowers as a Scotland Yard detective who, with his faithful companion — a stop-motion animated bug named MacGregor — is on the trail of the nefarious "Fuzz-Faced Phantom." Meanwhile the Phantom is at work hatching full-grown chickens from eggs, floating pots across rooms, and causing pants to dance on their own. In 2004 the Library of Congress named "There It Is" to the National Film Registry for its "cultural, aesthetic, or historical significance." You can find it on the DVD set More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931.)

(Note: Not included on this DVD, but worth mentioning all the same, is the 1928 short "There It Is." Directed by Harold L. Muller, it stars Bowers as a Scotland Yard detective who, with his faithful companion — a stop-motion animated bug named MacGregor — is on the trail of the nefarious "Fuzz-Faced Phantom." Meanwhile the Phantom is at work hatching full-grown chickens from eggs, floating pots across rooms, and causing pants to dance on their own. In 2004 the Library of Congress named "There It Is" to the National Film Registry for its "cultural, aesthetic, or historical significance." You can find it on the DVD set More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931.)

After 1940 Bowers drops out of history until his death in 1946, entirely forgotten. French surrealist André Breton wrote a piece lauding "It's a Bird," and years later that became a clue toward identifying the anonymous Bowers. In 1992, Lobster Films began a worldwide search to retrieve the surviving prints. Although Bowers was an American filmmaker, his rediscovery occurred through sources in France, the Netherlands, and Czechoslovakia. The French knew him as Bricolo, and that's how he is addressed in French source prints on hand here.

After 1940 Bowers drops out of history until his death in 1946, entirely forgotten. French surrealist André Breton wrote a piece lauding "It's a Bird," and years later that became a clue toward identifying the anonymous Bowers. In 1992, Lobster Films began a worldwide search to retrieve the surviving prints. Although Bowers was an American filmmaker, his rediscovery occurred through sources in France, the Netherlands, and Czechoslovakia. The French knew him as Bricolo, and that's how he is addressed in French source prints on hand here.

The appeal of these antiquities lies almost solely in Bowers' hypnagogic-dream imagination. They tend to dawdle and recycle favorite ideas, and as a director-actor he lacks the polish and charisma of his celebrated contemporaries. But his fusion of live action with model animation gave birth to creations that are wacked-out hybrids of Buster Keaton, Willis O'Brien, and that inimitable inventor himself, Dr. Seuss.

* * *

This two-disc DVD set preserves 15 of Bowers' comedies, totaling almost four hours, with commendable restoration work. Signs of age and wear vary throughout these vintage prints. "Now You Tell One" is fresh-looking while "Say Ah-h!" has moments of severe deterioration. But all things considered, these are in good condition with impressive clarity, contrast, and definition. Because of where the source prints came from, most of the films' intertitle cards are in French, with optional English subtitles turned on by default. As for audio, the "silent" films come with new Dolby Digital 2.0 monaural piano scores by Neil Brand. In addition, some have optional Dolby Digital 5.1 electronic or accordion scores (yes, you read that right), but those are at best irrelevant alongside Brand's jazzy, uptempo piano that fits the films like a glove. Most of Bowers' sound films come with their original English audio tracks in good condition, though a couple have lost their audio altogether.

Disc Two's big extra is Looking for Charley Bowers, an illuminating 16-minute French documentary about the few international film archaeologists whose detective work led to Bowers' resurrection. Also here is a brief photo gallery of high-quality stills and production photos, including shots from Bowers films that remain lost.

—Mark Bourne